By Holly Green

The human brain is an amazing tool. But there’s one thing it doesn’t handle very well – change. Especially change of the magnitude brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nobody saw this virus coming, but it has turned our world upside down. Our challenge as leaders is how we respond to it – a task made more difficult by the fact that the human brain did not evolve to deal with sudden and overwhelming change positively.

Humans are pattern seeking, structure loving animals. We prefer the known over the unknown, even when the known may not be as we would like it. So when a major change comes along, we go through a process much like grieving. First comes shock or surprise, followed soon after by denial. When it becomes obvious the change is real, we move to frustration and anger. This is often followed by depression and/or a lack of energy.

Only when we reach a place of acceptance can we begin adjusting to the new normal. Then we can move into transition and begin experimenting with new ideas and new ways of thinking that allow us to move ahead in a positive manner.

Why We Instinctually Resist Change

When massive change hits, our brains search for stability and predictability. They look for data that shows the change is just an illusion. In other words, we see what we want to see rather than what is actually happening in the world. This leads to traveling well-worn mental pathways that fit our view of the world but not the new reality. As a result, we make the same mistakes over and over, or we don’t adapt and adjust to address the new reality well. Then we wonder why our mental pathways now lead us astray instead of producing the results we want.

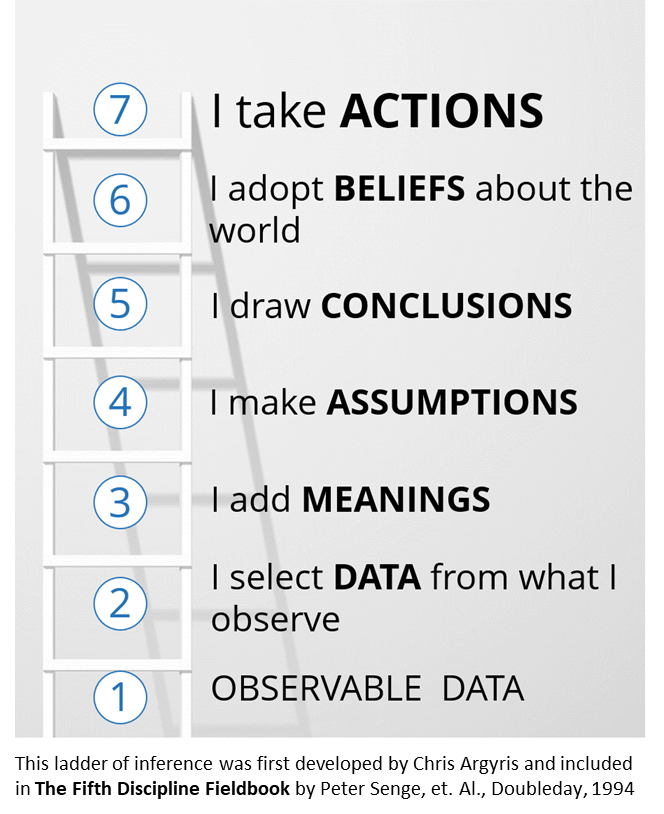

To understand how and why this occurs, let’s look at the Ladder of Inference, which outlines a process for how the brain guides us from thought to action.

When we witness an event, we take in observable data through our senses. The brain can only process so much data, so it selectively chooses what to observe and then adds meanings to the data. So far, so good except each of us is highly likely to screen in a slightly different ‘slice’ of the data we are screening in. Next, we make assumptions based on the meanings we attach to the data. From that, we draw conclusions based on the beliefs we have about the world. Now we’re ready to take action.

Here’s where we get into trouble. One thing the human brain absolutely excels at is proving itself right. Unfortunately it does this based on our assumptions and beliefs about how the world works. According to our brains, our beliefs are truth. Furthermore, the truth is obvious (because that’s what we’re looking for), so the action we take must be the right one.

The challenge is, our attitudes and beliefs are often a result of what our brain wants to see rather than what it sees. In times of change, when the world is full of ambiguity, we lean on our beliefs and assumptions rather than a rational assessment of the observable data. We select the data we believe while screening out data that contradicts our beliefs. And so we make bad decisions and take actions that keep us stuck in the past.

Today, rapid ongoing change is the norm rather than the exception. Our brains process this constant change as ambiguity, causing stress, anxiety, and a lack of focus. As wave after wave of change hits us, we continually start over in our response to change. This, in turn, can lead to a never-ending cycle of shock, denial, frustration, anger, and depression. To get out of this cycle, we need to use our brains differently.

Pause, Burst, and Change Perspective

Our attitudes and beliefs about the world are always based on data. And our brain processes opinions, speculation, and facts as data. Sometimes the data is correct; sometimes it isn’t. In today’s fast-moving business world, the longer we’ve held on to an old idea or assumption, the more likely it is no longer valid. And the more we tell ourselves something is so, whether it is or not, the more the brain processes it as data and acts on this ‘self-talk’ as a truth.

To adapt to change, we need to interrupt the brain’s process for turning data into action. This starts by taking a moment to identify what phase of the cycle you’re in, such as shock or anger. Then, pause at each rung of the ladder of inference to ask:

What if..

- I am wrong

- There is something else

- This is an opinion or hypothesis

- The data I’m selecting could be interpreted another way

- There is more I know/do not know about this

- Things have changed

Next, intentionally burst your “thought bubbles,” the unspoken attitudes and beliefs you hold to be absolutely true. The more successful you have been, the more your brain wants to hold onto the past. Bursting your bubbles allows you to unlearn old ways of thinking and open up to new ones.

To change perspective, expand your data sources. Go outside your business or industry to gather ideas from people who see the world differently. Spend 5 minutes proving yourself wrong. Without the intention to prod your brain to consider possibilities and options, your brain will continue proving the same old things right.

During times of uncertainty, people look to leaders to provide clarity and a grounded hope for a better future. It’s our job to model deliberate calm and balanced optimism while processing large amounts of complex information, contradictory views, and strong emotions. Think about what you’re thinking about. Pay attention to whether you’re making decisions based on just your bubbles or accurate data. Be open to new ideas. COVID will pass, but change isn’t going to slow down anytime soon. The companies that win during our rapid-change environment will be those with leaders who are intentional about how they think and act.

This article was originally posted at thehumanfactor.biz

Holly Green is a faculty member of LEADERSHIP USA.